|

|

|

|

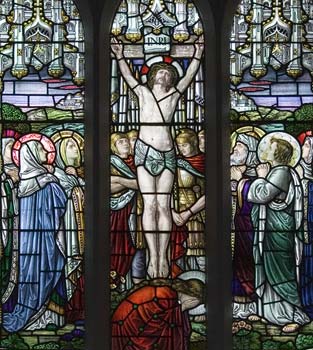

St Veronica At The Foot Of The CrossAn unusual compositionPainting by Francis Murray Russell Flint (1915–1977) St Mary’s Church, Fishguard was built in 1855–57 on the site of a medieval chapel, to the designs of an amateur architect, Thomas Clark of Trowbridge. The church is in an idiosyncratic Romanesque style, but contains several features of interest, including important work by John Petts (1986 and 1989) and Celtic Studios (1970). The painting, serving as a reredos to the south chapel altar, by Francis Murray Russell Flint, was given to the church at an unrecorded date in memory of Captain and Mrs F. Martin of The Towers, Fishguard, by members of their family. F.M. Russell Flint was the son of Sir William Russell Flint, R.A. (1880–1969), President of the Society of Painters in Watercolour, a medium which he had made particularly his own. Sir William was notable for his skill in depicting the nude and partially clothed female form. Examples would include his ‘Jemima in Anglesey’ and – a rare foray into a Biblical subject – the ‘Bath of Susannah’. A recurrent motif was his use of young, slender, dark-haired female models, as, for example, in his ‘Reclining Nude III’ and ‘Janelle and the Volume of Treasures’.(1) This, as will be seen, has some relevance to the picture under discussion here. At first sight, F.M. Russell Flint’s depiction of the crucifixion is notable only for the unusual arrangement of the figures, but closer examination reveals that the identity of one of those figures in particular marks a departure from the Biblical text. The foreground figure, standing in profile at the foot of the cross, is Veronica, holding the Sudarium, on which is prominently imprinted the face of Christ. The story of Veronica and the veil derives from late apocryphal texts, the Mors Pilati and the Vindicta Salvatoris, which are closely associated with the Gospel of Nicodemus. Here Veronica is identified with the woman healed by Jesus of an issue of blood (Luke 8 vv.43–48). The legend is that Veronica, filled with compassion at the sight of Jesus bearing his cross to Calvary, wiped the sweat from his face with a cloth. On that cloth there was imprinted an image of his features. The legend became immensely popular from the Middle Ages, and is the inspiration for Station VI in the devotion The Stations of the Cross. It probably derived ultimately from the recorded meeting on His way to crucifixion between Jesus and the women of Jerusalem, who bewailed his suffering. (Luke 23 vv.27–31).

Iconographically Veronica is almost always shown wearing a headscarf or coif, and holding the veil prominently displayed – as Flint has done here.(2) However, she is also almost always shown either in association with scenes from the Via Dolorosa, or, as in the Master of St Veronica’s Saint Veronica with the Sudarium of c.1415, now in Munich, as a solitary standing figure holding in display the sudarium before her. Russell Flint has departed from both of these traditions in the Fishguard painting by showing her standing at the foot of the cross. Here she actually occupies the place normally accorded to Mary Magdalene, whose presence at the crucifixion is attested by the gospel narratives (Matt.27 vv.55–56; Mk.15 vv.40–41, in both of which she is named; Lk.23 v.49, where she is not.) All three of these narratives, however, assert that the women stood “afar off”. Only John 19 v.25 places Mary Magdalene, with the Blessed Virgin Mary and Mary the wife of Cleophas “by” the cross itself, and it is this verse that has formed the basis of the iconographic tradition. In Flint’s painting, Mary Magdalene stands in the left foreground. The Magdalene’s hair is almost universally shown in art as uncovered and loose, as here, and in this painting her gaze is upwards, ‘striking’ the person of the crucified Christ at roughly the mid-point. This may be a covert reference to the tradition of an intimacy between Christ and Mary Magdalene, a tradition notably – if not notoriously – exploited by Eric Gill in his 1922 wood-engraving Nuptials of God.

Another notable feature of this painting is the total absence of the other major figures of the gospel narrative, the Blessed Virgin and the apostle John. A possible explanation is that here Flint is taking up the reference to the women standing ‘afar off’, and thus out of the frame of the composition, or, more likely, that he has interpreted Jn.19 v.27, that John, having been charged by Jesus from the cross to care for his mother, had “from that hour” taken her to his own home, and that therefore, by this time, they had both already left Calvary. The question of time is not irrelevant here. The background to the composition is a lowering and gloomy cloudscape. Read (as is usual) from left to right, the gloom is gathering, and this is a reference to Lk.23 vv.44–45, and thus sets the time of the painting to the beginning of the sixth hour, from which moment there was, according to the synoptic tradition, “a darkness over all the earth until the ninth hour” (Lk.23 v.44). There are two other points of interest. One of the Roman legionaries in the background is carrying a spear. Again, it is the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus which names this soldier. The legionary – whose lance was to pierce the side of Christ – was Longinus.(3) In John’s gospel (19 v.34) it was a nameless soldier who pierced the side of Christ, “and forthwith came there out blood and water”. It is also interesting to note here that the centurion, who at the death of Jesus “glorified God” for a “righteous man” (Lk.23 v.47) and as “the Son of God” (Mk.15 v.39; Matt.27 v.54) is shown prominently, mounted on a white horse. This is a device which had been used previously, for example, by Augustus John in one of his studies of the crucifixion.(4) Secondly, the positioning of the two crucified thieves (again, identified in Nicodemus as Demas and Gestas) at first sight seems strange,(5) Christ’s cross is set between those of the two thieves, but Flint has placed it so that it was possible for Jesus to see only one of the two men. He could therefore address the one on his left (Lk.23 vv.42–43), the penitent who is promised Paradise. The penitent could also shout across to the impenitent (vv.39-41), but Flint has noted that there is no direct or recorded exchange between Jesus and the impenitent thief, and thus has placed him, significantly, behind him, where the shadow of the sixth hour darkness is already falling. By contrast, the dying light falls fully on the figure of Jesus. (According to Lk.23 v.44 it was after the exchange with and between the thieves that the darkness fell.)

A final word should, perhaps, be said about the figures of Veronica and Mary Magdalene. It is interesting to see how closely the models resemble those favoured by Russell Flint’s father, Sir William. A comparison could be made between the (right profile) standing figure of Mary Magdalene here, and the (left profile) standing figure ‘Maggie – Posing” by Sir William. And, although her hair is largely hidden by the coif, it is clear that the model for Veronica was also of the slender, dark-haired kind favoured by the father. The painting is a most interesting interpretation of the gospel narratives, carefully composed, but with Veronica rather than the crucified Christ as the central figure in the lower part — Christ’s cross is offset right of centre. It certainly repays very careful study. John Morgan-Guy 1. His models in Jemimah in Anglesey, the Bath of Susannah, and – a very similar piece – In Classic Provence would all also come into this category. 2. The name ‘Veronica’ itself means “true image”, and this may indicate that it was transferred from the veil (vernicle in English) to a previously anonymous compassionate woman in the legend.

|

F.M. Russell Flint, Crucifixion, unknown date, Church of St Mary Fishguard. © Estate of the artist

|