The Adoration of the Magi

(Matthew 2 verses 1–12)

At St Peter's Newchurch, Monmouthshire

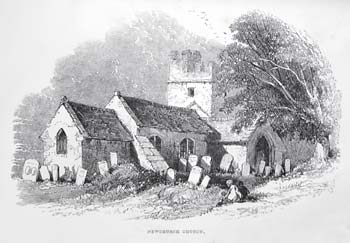

The church of St Peter stands in an exposed position on a ridgeway, to the north-west of the town of Chepstow. Although a medieval foundation, the name was almost certainly intended to differentiate it from the church of Kilgwrrwg, in origin of much earlier date, set in a very isolated position in the valley to the north.

The historic parish of Newchurch was of large acreage, and though now almost entirely rural, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in its eastern portion had a sizeable population, many families being dependant upon the Tintern Iron and Wire Works for their livelihood.

A drawing of (probably) the 1840s shows the medieval church to have been in some disrepair, and, having been – with the exception of the tower – demolished to its foundations, it was rebuilt in a simple Decorated Gothic style by J.P. Seddon in 1863–1864. The fabric of the church has remained substantially unaltered since then.

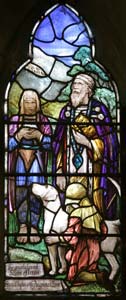

The only stained glass in the church is to be found in the east window, set in Seddon’s two trefoiled lancets and the roundel above. The glass was designed by THEODORA SALUSBURY, and is an arresting and unusual interpretation of the story of the Adoration of the Magi contained in chapter 2 of St Matthew’s Gospel.

The Artist: Who was Theodora Salusbury ?

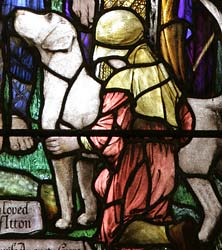

Theodora Salusbury (1875-1956) was a native of Leicester, where her father was a solicitor. The Newchurch window is her only work in Wales. The window at Newchurch dates from 1931, and, as the inscription says, was placed here in memory of “the greatly loved squire of Itton” Sir William Edward Carne Curre, Bt. (1855-1930) by his wife Augusta. Itton is a neighbouring parish to Newchurch, and the Curre family of Itton Court owned property here. Sir Edward’s memorial, designed by Guy Dawber, is to be found in the chancel of Itton Church.(1)The separation of that monument from the window may give some substance to the local story that the then rector of Itton took exception to the design of the window, because it included a foxhound, and refused to allow it to be placed in that church. Theodora Salusbury was one of a notable group of women stained-glass artists associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement. She studied as a mature student at the London County Council Central School of Arts & Crafts, where she attended Karl Parsons’ stained-glass course. She may also have worked briefly with the ‘doyen’ of Arts & Crafts stained-glass artists, Christopher Whall, before setting up her own studio in Kensington. Certainly, her Newchurch window shows that she was at least familiar with Whall’s famous text-book, Stained Glass Work, published in 1905. Salusbury designed and painted her own glass, but the firing and glazing were carried out by Lowndes and Drury at ‘The Glass House’ in Fulham. This workshop had been set up in 1897, at first in Chelsea, by Mary Lowndes (1856-1929) and Alfred Drury, formerly Head Glazier witth the firm of Britten & Gilson, where Lowndes had begun her professional career. ‘The Glass House’ for a number of women stained-glass artists, like Theodora Salusbury and Lilian Pocock, one of whose windows can be seen at Llanfachreth, Anglesey(2). As might be expected, most of Theodora Salusbury’s windows are found in and around her native Leicestershire. Her Newchurch window reveals a talented artist of some originality.(3)

The window: left lancet

The left lancet (when facing the altar) contains figures of two of the Magi.(4) They are accompanied by the kneeling figure of a young boy, possibly a servant, though perhaps intended as a youthful shepherd – thus balancing the kneeling figure in the right lancet. If Newman’s identification of these figures as shepherds is correct,(5) then the artist in her design is conflating the narrative of the visit by the shepherds to the new-born Jesus in Luke’s gospel (ch.2 verse 16) with that of the adoration of the Magi in Matthew. Interestingly, however, she depicts the “shepherds” as children, and here there are echoes of two other Arts & Crafts designs in Wales. At nearby Wolvesnewton, the angels surrounding Mary and the infant Jesus in the east window (1924) are shown as children, and the Angel of the Annunciation in Henry Wilson’s beaten copper frontal for the altar at St Mark’s, Brithdir, Merionethshire (1895-98) is also depicted as a child. Is this a particular Arts & Crafts conceit ?

The two Magi in the left lancet are shown with gifts. The figure on the left, seen in profile, is in the act of raising a golden crown as an offering. The first of the gifts mentioned by Matthew is that of gold, which, as the Epiphany hymn notes “a royal child proclaimeth”. The second magus, shown in portrait, holds a casket – presumably, if the traditional order of the gifts is here maintained – containing frankincense. (“Incense doth the God disclose”.) On the grass between these two standing figures is a lantern, perhaps a homage to Holman Hunt’s iconic painting of Christ as “the Light of the World” but certainly a reference to the biblical text that inspired it (John 8:12). This ‘light’ is itself an epiphany (revelation/ manifestation) as the description is Jesus’ of Himself, and continues with the assurance “Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life”. This is both the challenge and the promise of the Epiphany, the festival (6th January) which in the western catholic tradition commemorates the adoration of the Magi.

The form of the golden crown offered by the first magus should be noted. The design bears a close resemblance to interleaved thorns. It may thus be seen as a “type” of the crown of thorns (Matthew ch.27 v.29) set on the head of Jesus by Pilate’s mocking soldiery before the crucifixion. The window thus contains a “forward reference” to the Passion, a theme taken up in the second lancet.

The window: right lancet

Here again (balancing the left lancet) there are three figures. On the extreme right is an elderly magus, holding – but not offering – a crown similar in design to that depicted in the left lancet.(6) The gift of this, the third, magus, another casket, is held by a servant. This is myrrh (“a future tomb foreshows”) the preparation of a gum used in the embalming of corpses. Again, as with the “thorny crown”, this is a forward reference to Jesus’ Passion and sacrificial death. There is nothing in the design of the casket to differentiate it from that held by the king in the left lancet, but the solemn – indeed, grim – expression on the face of the servant probably indicates the nature of the gift.

The two lancets are in perfect balance. The magi on the extreme left and extreme right are shown in profile or semi-profile, the two inner figures in portrait. In the foreground are the two kneeling figures, that on the left in profile, that on the right from the rear. As in the left lancet there is the lantern, on the right, behind the servant, there is a small representation of Bethlehem. Traditionally the locus of the Nativity and of the Epiphany, the reference is to Matthew ch.2 vv.4-6, where Herod is reminded of the prophecy in Micah ch.5 v.2 that in Bethlehem the Messiah would be born. But where is the figure of that Messiah ?

The window: the roundel

Perhaps the most striking and moving element in the whole composition, it is here, and not in the main body of the window, that we find the Christ-child. The Virgin Mary is shown seated upon the throne of the heavens, her arms outstretched, the right hand holding the hem of her cloak in such a way as to protect the head of the child that rests in her lap. The mother’s gaze is downwards, to the child, but the infant looks outward, intently, towards the observer. With his left hand he clutches the robe of the Virgin at her breast, but with the right points downwards, though, interestingly, at nothing specific. If a line is drawn from the index finger, it meets the left lancet neither at the point of the offered gold crown nor at the upward, adoring gaze of the kneeling shepherd-boy. If at anything specific, the finger points down to the inscription at the base of the window, recording its erection by Lady Curre in memory of Sir Edward.

The figures of mother and child are very well observed. The Virgin is shown as a young girl (by tradition the Blessed Virgin was in her early ‘teens at the time of the Nativity) and the child, with chubby limbs and crossed legs certainly could have been drawn from life. Seated above the heavens, with five (possibly six) stars, against the background of a golden orb, there are hints in this depiction of the woman of Revelation 12:1 (“A great and wondrous sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head”) though the parallels are not exact.

Of particular interest in the roundel are the two flights of birds, appearing as ghostly images in the grey area below the Virgin’s feet. It is inotable that Sir Guy Dawber included birds flying across the ceiling in the barrel-vault of his chapel at Matlock Bath. Is there a connection here ?

The window design has two further points of interest. In the right lancet, the kneeling shepherd-boy gently restrains a white foxhound. The hound is said to have been the favourite of Sir William, for whose Curre Hunt Guy Dawber had in 1893 designed the stable and yard at Itton Court.(7)

Both the left and right lancets, in their borders, include the device (very small, and insignificantly placed) of a peacock, in full display, in purple glass. In Christian symbolism the peacock represents immortality, “either owing to a belief mentioned by St Augustine that its flesh was incorruptible, or perhaps because it sheds its tail feathers every year, to regain them more gloriously in the spring”.(8) Such a symbol is appropriate for a memorial window, but the unusual colour, the repeated motif, and its placing in the borders may indicate that this is the ‘signature’ of the designer or manufacturer.(9)

With its glowing colours, and striking design – which makes the best possible use of Seddon’s rather heavy and uninspired fenestration – the window ranks high in the list of Arts & Crafts’ interpretations of a Biblical narrative in Wales.

John Morgan-Guy

November 2005

Church of St Peter, Newchurch

Similarities between Camm, Salusbury and Davies of the Bromsgrove Guild

1. Sir Guy Dawber (1861–1938), was a moving spirit behind the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, and the architect of a number of notable country houses. He is, perhaps, best known as the architect of the Reptile House at London Zoo (1937) and the Zoo’s main gate. A leading ‘Arts and Crafts’ designer, he built the remarkable private chapel of St John the Baptist, Matlock Bath, in Derbyshire, now in the care of the Friends of Friendless Churches. As a young man, between 1893 and 1896 he undertook major work at Itton Court for the Curre family, and seems to have maintained a connection with them for the rest of his life. John Newman says that Dawber’s enlargement of Itton Court was “the first full-blown Arts & Crafts scheme” in Monmouthshire. It is not, therefore, surprising to find a memorial window at Newchurch in accord with the principles of the movement. (John Newman, Gwent/Monmouthshire The Buildings of Wales, University of Wales Press, 2000, p 66.

2. Ann O’Donoghue, ‘Mary Lowndes – a brief overview of her work’, Journal of Stained Glass, XXIV (2000–1) pp 38–53; Peter Cormack, Women Stained Glass Artists and the Arts & Crafts Movement (London Borough of Waltham Forest Libraries & Arts Department, William Morris Gallery, Exhibition Catalogue, 1985).

3. I am grateful to Peter Cormack, Keeper of the William Morris Gallery, for kindly providing information on the life and career of Theodora Salusbury.

4. By tradition there are three magi – an inference from the the three gifts mentioned by Matthew (ch.2 v.11). The evangelist, however, makes no specific mention of three magi. Salusbury’s window follows tradition, with the three magi depicted over the two lights.

5. Newman, op.cit. p 420.

6. Again by tradition the magi have been identified as “kings”. Cf. Psalm 72 vv.10–11 “The kings of Tarshish and of distant shores will bring tribute to him; the kings of Sheba and Seba will present him gifts. All kings will bow down to him and all nations will serve him”. Tarshish was one of the sons of Javan (Genesis ch.10 v.4) from whom “the maritime peoples spread out into their territories by their clans within their nations, each with its own language” and thus one of the ‘ancestors’ of the gentiles. The homage of the magi stands for the gathering in of the peoples, Jew and Gentile, alike, in the worship of the Messiah — “the light to lighten the Gentiles and…the glory of…Israel” (Simeon’s acknowledgement of the infant Jesus in the Temple, Luke ch.2 v.32). The lantern in the left lancet can also be seen as a coded reference to this prophecy.

7. There is another example of the inclusion of a favourite dog in a memorial window at Llanfair-ar-y-bryn, Llandovery. Here in the south wall of the chancel is the 1965 window by John Petts depicting St George overcoming the dragon. The window is in memory of John Logan Stewart, killed at Dunkirk in 1940, and given by his parents. The design was suggested by Stewart’s sister, Mary Elizabeth Halliday; the face of St George is that of her brother, and the design also includes the head of his favourite dog.

8. Arthur H Collins, Symbolism of Animals and Birds represented in English Church Architecture (London, Pitman & Sons, 1913) pp 137–138.

|

Theodora Salusbury, The Adoration of the Magi, 1931, Church of St Peter, Newchurch Theodora Salusbury, The Adoration of the Magi, 1931, Church of St Peter, Newchurch |

Theodora Salusbury, The Adoration of the Magi, 1931, Church of St Peter, Newchurch

Theodora Salusbury, The Adoration of the Magi, 1931, Church of St Peter, Newchurch